Reflections: Meaningful Encounters in Play

Meaningful Encounters in Play – A Story of Practitioner Inquiry at Gowrie NSW

Meaningful Encounters in Play – A Story of Practitioner Inquiry at Gowrie NSW

By Jessica Horne-Kennedy, Manager Professional Learning, Gowrie NSW

Over the past year, and continuing into this one, the educators across our eight Early Education and Care Centres at Gowrie NSW have embarked on a project of deep inquiry guided by pedagogues Wendy Shepherd and Janet Robertson. The ‘Practitioner Inquiry Project’ (PIP) – is described by Janet and Wendy as “provocation for contextually changing spaces, relationships and thinking about the environment including the consideration of beauty in each of the Gowrie Centres in NSW” (Personal Communication, 2020).

Through this article, the story of this project as it has and continues to unfold will be told. The perspective I will share is one of ‘looking in’ informed by listening to, observing, and reading the rich collection of examples that document this project.

Entry Points – Translating and Embedding Gowrie NSW Program Foundations

The Gowrie NSW Program Foundations provide an outline of the pedagogical practices seen collectively as the underpinnings of quality early childhood learning environments (Arthur, 2020). The entry point for the Practitioner Inquiry Project (PIP) arose from conversation about the ‘Gowrie Foundations’ particularly how to translate and embed the espoused beliefs of this document into daily practices of working with children and families. By honing in on the foundational area of ‘Intentional Play-Based Teaching’ discussions between our mentors – Wendy and Janet, our CEO – Nicole Jones and our Executive Director of Pedagogy – Michelle Richardson led to reflection about the learning spaces children would experience at Gowrie NSW. This vision is articulated in the following from Gowrie NSW Program Foundations:

“Since its inception, Gowrie NSW learning spaces have been designed to facilitate play-based learning. Easily accessible resources on open shelving indoors and flexible moveable parts in the outdoor environment, support children’s access to loose materials for their own spontaneous play as well as planned play sequences (…). The Gowrie NSW learning environment has always encouraged children to explore nature with large trees, long grass, vegetable gardens and a range of animals. Learning environments are designed to facilitate exploration, hypothesising and discovery, to nurture children’s sense of wonder and to support connections to the natural world and understandings of sustainability.”

(Arthur, 2020, p.12).

Shaping spaces: the possibilities for pedagogy, play, learning and relationships.

The first step into this project focused on time for each service to connect with mentors Janet and Wendy and to begin a process of collaborative discussion with their team colleagues. Beginning to collect thoughts, images, and ideas about the environment that children and educators inhabit each day provides possibilities to deepen collective understandings about the “…critical role that the environment plays …” in building funds of knowledge to inform practice and pedagogy. (Personal Communication with Janet Robertson and Wendy Shepherd, 2020). At this first stage, the formation of new relationships between educators and mentors was an important step that soon travelled into a new territory where educative teams began to consider the “… responsive and reciprocal relationships with people, places, and things …” (Ministry of Education, 2017, p.21). The learning and care environment began to be reconceptualised to see spaces as unique assemblages – innovative spaces that allowed “…objects, humans, ideas and discourses [to] meet and collide” (Charteris et al., 2017 cited in: Somerville and Powell, 2019, p.838). In this way, and as (Mulcahy & Morrison, 2017) describe:

“Re/assembling ‘innovative’ learning environments’ is concerned with how these spaces function as assemblages of relations and most particularly, affective relations. Assemblages are produced by affects that emerge through embodied encounters between subject and object, person and world. Such assemblages afford attention to how intensities of feeling can gather around and be provoked by objects as evidenced in the empirical material where walls that serve to either open or close learning spaces are shown to activate affect.”

(pp. 756–757).

Remembering Children’s Encounters with Blocks – The Role of Block Play.

As an observer of the Practitioner Inquiry Project, I was witness to the pedagogical fragments being explored in practice. One such fragment that I heard about and observed was the investigation into block play. I was curious and my curiosity took me back to my memory as a teacher at Glenaeon Rudolf Steiner Preschool. In this memory, I could see myself, with my basket of soft cloths and my jar of lavender infused polishing oil. It is a rainy day, and I am sitting in the corner of the room to anchor the play, ready to begin my work of polishing the blocks from the block shelf. As, I begin this work, some children join me and help to gently oil each block. While other children, come to see what is happening then move to play after finding the blocks they need to add to their city or other imaginative creation.

Revisiting this memory provides a connection to ‘Master Class Two’ where Janet and Wendy shared that:

“It is important to create a ‘block culture’ within the Centre. Where adults and children revel in block work, where it is a valued and rich form of play and learning, provided every day in every space, understood, and respected by adults as a nongendered equipment and space, and the social ‘rules’ of play are clear for all. Blocks will only thrive in a Centre that understands and values their contribution to children and adults thinking. A block culture depends on what your pedagogical values are”

(Shepherd and Robertson, 2020).

Allowing the block culture to thrive at our eight Gowrie NSW centres involved key steps of inquiry such as:

- Photographing the ‘block areas’ to consider how blocks were or were not given reverence

- Reflecting about the forms of learning that block play enabled, and

- The vocabulary adults could use to facilitate and prompt children’s imaginative exploration of this resource.

Through the Masterclass, educators were introduced to the rich, holistic learning that is possible through enabling a culture of inquiry through block play. Within each centre, educators began to notice children engaging in new and diverse ways with blocks and the language educators chose to describe this engagement highlighted children’s engagement, creativity and collaboration across many domains of learning. Educators described how children were using blocks to do more than just ‘build’ but to develop their imaginative thinking.

“I have enjoyed watching how the children use the blocks to do more than ‘build’. Our children have used them as slides for animals and fences as well. Developing their imaginations.”

(Personal Communication – Leonie Derrick, June 2020).

Other educators observed how children explored roles and collaborated to extend and connect concepts of their world and community.

They built a city with one child being the town planner and others following and adding their own ideas. More children came over and added some details such as red traffic lights as well as animals ‘because sometimes we see kangaroos when we are out! (Personal Communication – Mikaela Plessnitzer, November 2020).

Many diverse structures appeared in the children’s explorations from a rabbit cage, to houses, walls, bridges, a prison, and stations. At one service, block play enabled partnerships with the centre community as a parent noticed the children’s interest and shared their knowledge and passion of architecture.

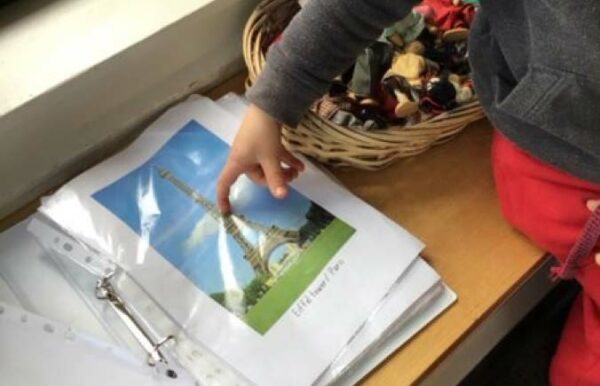

A family member noticed the children’s interest and was excited to give us more plans and sketch paper. The family member was then invited to the service, to talk to the children about architecture and architectural plans. Through this, we encouraged the children to look at [pictures and photographs of] the buildings in the folder and draw what (they think) it looks like. From this, we decided to challenge the children to build a structure with the blocks, … taking some time to draw it out. Extraordinary work and children’s observations allowed little details to be sketched by each child.

(Personal Communication with Mario Boustani, October 2020).

Anne Schiller says that: “The most important thing a teacher can do to facilitate block play is to have great interest and reverence in blocks. It can’t just be that you›re leaving the blocks passively on the shelves hoping that [the children] will discover them. … Blocks are something you help children to discover. You show them. You discover blocks alongside them.”

This reverence for block play can be seen in the different ways that educators invested time in preparing spaces or ‘block worlds’ and even extended to some educators taking the time using their strengths to create a treasured resource for the children to use in their play.

The Practitioner Inquiry Project (PIP) is an ongoing inquiry in process. This story highlights how through intentional connection with, and examination of the materials in the play environment children are able to express the signs of

“…sustained engagement – excitement, intensity, vitality – where the senses and the child’s body are fully immersed in what they are doing”

(Somerville and Powell, 2019, p. 835).

In this way educators are recognising how to respond to play and embed the practice foundation of ‘Intentional Play-Based Teaching’. In providing the opportunity for educators to engage in practitioner inquiry we are developing and shaping a culture of inquiry that draws from the historical origins of our organisation. This growth is twofold seen in the pedagogical identity as an organisation as well as the professional identity of the educators and teachers engaged in this project.

Reference List

- Arthur, L. (2020). Program Foundations. Sydney: Gowrie NSW

- Margaret Somerville & Sarah J. Powell. (2019) Thinking posthuman with mud: and children of the Anthropocene, Educational Philosophy and Theory, 51 (8), 829-840.

- Ministry of Education, New Zealand. (2017). Te Whāriki. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

- Mulcahy, M., & Morrison, C. (2017). Re/assembling ‘innovative’ learning environments: Affective practice and its politics. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(8), 749–758.

- Robertson, J. & Shepherd, W. (2020). Blocks Master Class (Power Point Presentation for Practitioner Inquiry Project – Gowrie NSW).

- Schiller, A. (2018). The Role of the Teacher in Block Play. Community Play Things. Retrieved from: https://www.communityplaythings.com/resources/%20articles/2018/the-role-of-the-teacher-in-block-play